Journalism student Carolin Wollschied in the USA | 01.09.2019

A journey into the land of disinformation

Journalism student Carolin Wollschied travelled from Mainz to the USA for a fellowship on disinformation in the media. In addition to visits to renowned American media, the programme also included workshops in journalism schools. What is the state of the debate - and what can journalism do in the fight against disinformation?

The news reaches me as I am standing at check-in at New York-Newark Airport: a manipulated video of Nancy Pelosi is spreading on social media. In the video, the Democratic Speaker of the US House of Representatives appears drunk and not sane. It was shared by close advisors of US President Donald Trump, among others. It was viewed over two and a half million times on Facebook. The original video was slowed down so that Pelosi appears drunk - and therefore looks bad in public. The moment I read this news, I realised once again how important my trip to the USA, which I was on my way home from, was.

But let’s start from the beginning: I’m Carolin Wollschied and I’m in my fourth master’s semester of journalism at Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz. As part of my studies, I was one of 16 German and American journalism students to take part in the “Journalism in the Era of Disinformation” scholarship programme in May, funded by the German Federal Ministry of Economics. The topic: disinformation in the media. Over the course of a week, we discussed this topic with representatives of large, small, regional and national American media in Washington D.C., Annapolis and New York. One goal was to develop strategies to increase trust in reputable media and counter disinformation. To this end, workshops were held at the University of Maryland and the City University of New York.

Carolin Wollschied (second from right) and the 15 other scholarship holders with Professor Sarah Oates at the Philip Merrill College of Journalism at the U of Maryland (Photo: Jorge Bagaipo).

At the beginning of the fellowship, it was important to clarify what disinformation actually is, what the difference is to misinformation and what the buzzword “fake news” has to do with it. Misinformation is information that is factually incorrect and is shared regardless of whether there is a specific interest behind it. Disinformation, on the other hand, is deliberately misleading, false or manipulated content. In a report, the British Parliament defined “fake news” as “the deliberate creation and sharing of false or manipulated content that is intended to deceive or mislead, either to cause harm or to make a profit.” Accordingly, fake news is also disinformation.

Do we have a “bad news problem”?

Even before I travelled to the United States, I was aware that the topic is perceived and treated differently in the US. Due to the president’s constant accusations of fake news against media that he doesn’t like, the issue has a different relevance than in Germany. However, it also plays a greater role because there is a political divide between Republicans and Democrats running through the country, who attack each other - sometimes with disinformation and manipulated content.

One of the most important findings of the fellowship was that it is best not to use the term “fake news” at all. Is the information deliberately false or manipulated? Then say “disinformation”. Fake news has become a politically charged term. Trump uses the term for everything he doesn’t like about media reporting. David Mikkelson, founder of the fact-checking website Snopes.com, said: “We should look for a different term.” Mikkelson goes so far as to say that we don’t have a “fake news problem”, but a “bad news problem”. This includes not only manipulated content, but all forms of disinformation: misleading, fraudulent, invented content, satire (yes, even satire is usually factually incorrect) and content in the wrong context or with the wrong connections.

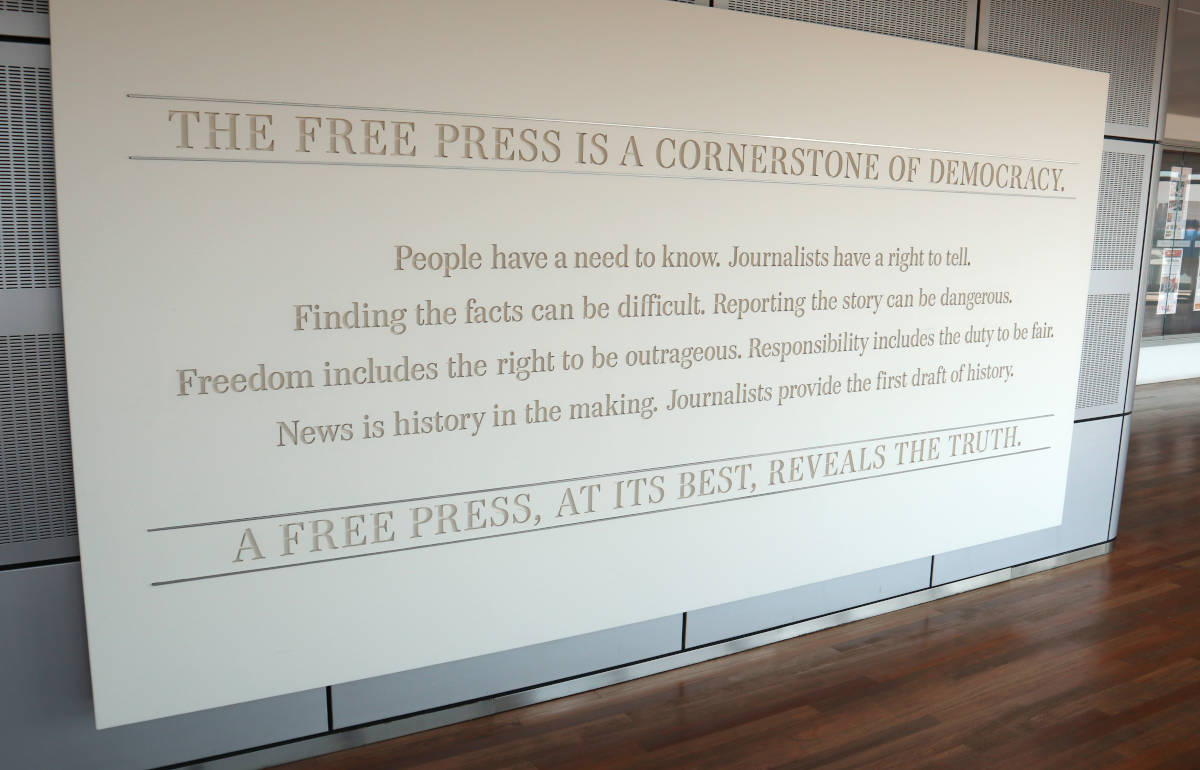

Freedom of the press is also a cornerstone of democracy for American students. This plaque is located in the Newseum in Washington D.C.

Even in Europe and Germany - without a president who discredits a large part of the media - the fear of disinformation is great. Before the European elections, a representative study on fake news by PwC revealed that more than two thirds of Germans see it as a threat to the European elections. One in four consider it likely that they will not recognise fake news and will be influenced by it when casting their vote.

The Germans’ fears are justified. Thanks to the internet, social media and an increasingly fast-paced media world, disinformation is easier than ever. Any of us can easily create false reports and spread them via social media. Even videos are no longer safe from this. So-called deep fakes can realistically depict manipulated videos. It can happen that Barack Obama says in a Buzzfeed video: “President Trump is a total and complete dipshit.” AI technologies make it possible.

Young people in Macedonia were able to influence the US election campaign with false information

Our use of media further exacerbates this problem: online in particular, we often only read headlines in order to scroll through them as quickly as possible. A second - closer - look at a video? Probably not, especially if the content also supports our own political opinion. This is probably how the manipulated video of Nancy Pelosi achieved rapid fame.

In 2016, young people from Macedonia demonstrated how easy and even lucrative it is to spread disinformation in the media. In the run-up to the US elections, they set up websites that spread false information about the USA - and made thousands of dollars in the process. The false news was in favour of Trump, as it generated more clicks. And there was money to be made from the advertising on the websites. The young people had no interest in politics or journalism. They were only interested in making as much money as quickly as possible.

Such developments harbour great dangers for journalism, society and democracy. A study by the Reuters Institute of Journalism has shown that many people who use news via social media or news aggregators such as Google News or Flipboard do not associate the news with the source, but with Facebook or the news aggregator. Instead of “I read this on FAZ.NET”, it is now just “I read this on Facebook”.

However, many people are also aware that they need to be careful online. Trust in news disseminated via social media on the internet is low, while trust in traditional media such as public broadcasting and daily newspapers is significantly higher, as shown by the long-term study on media trust conducted by Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz in its 2018 survey wave. At the same time, however, media and news usage is increasingly shifting to the internet, and the established news media must try to assert themselves as credible brands there too. Young people in particular use the internet as a source of news.

What can be done about the large amount of disinformation?

In an interview during our fellowship, Washington Post political reporter Aaron Blake advised journalists and the media to work transparently - especially when dealing with mistakes. However, an important step can also be to disclose research and link sources on the internet.

Aaron Blake from the Washington Post in conversation with the scholarship holders

Aaron Blake also spoke about “making newsrooms more culturally diverse”. The majority of American journalists are white. The cultural diversity of the USA is hardly reflected in most of the country’s newsrooms. This demand also exists in Germany. Back in 2017, Dpa editor-in-chief Sven Gösmann said that there should be “a little more Marzahn and a little less Berlin Mitte” in the newsrooms. The aim behind this is to reflect society as a whole, not only with journalistic content but also in production. This could be an important step in the debate about credibility and trust in the media.

The simplest and perhaps most efficient way to uncover false information on the internet is to use fact checkers. The ARD fact finder or fact checks by Correctiv show how it works. However, in order to reach as many people as possible, more media outlets should carry out such checks or use editorial teams to do so. The results could also be published in the traditional media instead of just online.

Another important point in the fight against disinformation is the use of social media. For many people today, it is the only source of news. However, Facebook and Instagram do not delete manipulated videos, and there are also repeated complaints on Twitter about the company’s blocking and deletion policy.

The slowed-down video of Nancy Pelosi remained on Facebook for weeks. In the meantime, the Facebook page with the video can no longer be found. However, this is probably not due to Facebook’s reaction. The company told the Washington Post that it wanted to “greatly reduce” the display of the video in users’ news feeds. In addition, there were pop-ups showing the results of two fact-check pages and warning users not to share the video. However, users were still able to share, like and comment on the video. “There is no policy that says the information published on Facebook has to be true,” said the Facebook spokesperson.

After these events at the latest, it was clear to me that anyone who wants to fight disinformation in the media and on the internet can do a lot - as a media user, as a journalist, as a citizen. But without co-operation with the big players on the Internet such as Facebook or Google, the problem will not be contained in the short or long term.